Thanks to Kate, one of the volunteers in the archive, for researching and writing this post.

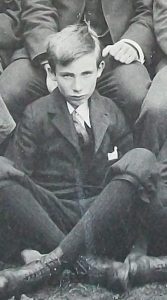

William Fryer Harvey was at Bootham from 1898 to 1901. He was born in 1885 into a prosperous West Yorkshire Quaker family. His father and brothers were also at Bootham and his sister a pupil at The Mount. Having studied at Balliol College Oxford, William then took a degree in medicine at Leeds. He joined the Friends Ambulance unit in 1914 and served until 1916. In 1918 whilst serving in the Royal Navy as a surgeon-lieutenant, he was involved in a rescue from the boiler room on board ship. For his bravery he was awarded the Albert Medal for Lifesaving and the full citation can be read in Bootham magazine, Summer 1918. Sadly this incident damaged his lungs and he never again regained full health, dying at the early age of 57. Amongst his many achievements the one for which he was probably most well known during his lifetime was as the published author of “supernatural tales”. One of the most famous was “The Beast with Five Fingers” and this was made into a film with Peter Lorre in 1946.

The archives contain a number of items written by him during his years at school. The collection includes letters to parents and his brothers both from school and whilst on holiday and a beautifully bound exhibition piece entitled “A collection of leaves”. There is also a volume of natural history observations and a two-volume diary of 1899. The handwriting is easy to read and there a number of very good pencil sketches and coloured illustrations of leaves, flowers, plants and the various churches and houses he visited. Reading through these it is interesting to ponder what hints there are in the schoolboy writings for the direction his life took after leaving Bootham. Certainly there is mention of many medical issues – scarlet fever, measles, colds etc are mentioned and in one letter he relates how a fellow scholar “ fell down in a fit during science going black in the face”. Happily after medical assistance, the boy recovered quickly enough to be playing football later in the day! He exhorts one of his brothers, studying in France, not to “catch smallpox from books” there and when his sister is taken ill, he writes to his brother that “her mind has given way probably from her studious habits” and says they should take this as an example “not to overwork themselves for fear of a similar fate befalling us”. However it is obvious that he has not taken this to heart, as prolonged study would have been needed to gain his medical qualifications.

From reading of his later life, his love of church architecture and the natural sciences seem to have been lifelong interests and I hope he kept the enquiring mind, which is illustrated, in the following extracts from the diary, written when he would have been around 13 years old.

“June 26th. I performed the following experiment to show that flowers on respiring produce carbon di oxide; by respiring I mean the taking in of oxygen. I took a number of common garden flowers such as marigold, blue corncockle, rose and placed them in a flask, being kept in position by a plug of cotton wool. I placed the flask in an inverted retort stand and placed a cork in the neck of the flask through which a glass was put open at both ends; one end of glass tube dipped in mercury on the top of which floated a solution of potassium hydrate. This solution absorbed the carbon di oxide given out by the flowers and the mercury rose about half an inch and a half.

I took some petals of a red rose and boiled in water; after some minutes the petals completely lost their colour and the water was coloured green and still possessed to a slight degree the scent of the rose.

July 1st – 6th. When removing the flask containing the flowers used in the experiment, a drop of acid happened to touch the blue flower of the corncockle and at once it turned a bright crimson red. I tried putting some more of the acid (sulphuric) on the flowers again and in each case obtained the same result. I then took some red GERANIUM and blue CRANESBILL and placed a few drops of ammonium hydrate on the red geranium and some dilute acid on the blue cranesbill. The colours of the flowers were reversed, the geranium becoming a bright blue though the change was not so quickly accomplished as in the case of the cranesbill.

It appears that certain flowers have the property of acting as an indicator of acids and bases in the same manner as litmus.

When the coloured petals were boiled in water until colourless, the water was slightly coloured blue and red.

On one drop of acid and ammonia being added to each, the colours changed and when acid and ammonia were added in the reverse order, the coloured water went back to its original colour.

The flower of a FUCHIA I examined had two sorts of petals; -the outer being red, the inner purple. But where the base of the inner purple petals touched the red ones, it was streaked with red. These purple and red petals acted in the way as those of the geranium and cranesbill. Perhaps the nearness and greater acidity of the red petals had something to do with the reddening of the base of the purple petals”