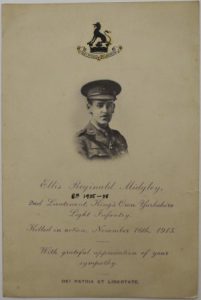

Ellis Reginald Midgley (Bootham 1905-08). Killed in action, November 16th 1915. Second Lieut. Born in Leeds, 1891.

From Bootham magazine, December 1915:

He had joined the Leeds “Pals” Battalion on its formation and received a commission in the 2/5th Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry six months before his death. Soon after leaving school he became an enthusiastic member of the Leeds Boys’ Rifle Brigade, and in more recent times he was a keen worker for the Y.M.C.A. His “Bene Decessit” speaks of him as archaeologist and football player. He kept both characteristics to the end. His last letter to the Headmaster was from the Colsterdale Camp on some archaeological point; he was secretary of the Northern Foxes F.C., and was no infrequent visitor playing against the School. He left Leeds on October 16th, having married a few weeks earlier.

He sent letters to “various members of the family almost daily, all bright and cheery, making light of the hardships and never a gloomy word.” In his first letter from the front he wrote:

We left Southampton Tuesday morning, October 19th, at 6.30, reached Havre (our base) at 1.30, left Havre 4 p.m. Wednesday, and had about 24 hours in the train. Thursday night we slept at the farm where our transports are, away behind the line 5 or 6 miles. It was there where I first heard the guns. Friday morning we reported, and I was sent out to “C” along a communication trench about a mile long, called “Halifax Road.” The firing line is about three-quarters of a mile in front of us. There was a very furious artillery duel on when I arrived which lasted till dusk; shells of all kinds and sires were dropping around, but none fell really near. The shells did very little damage. Bullets from rifles and machine guns are pretty plentiful, but do very little harm. I have a champion little dug-out, but we are not allowed any kit here, only what we wear and one blanket, so it was jolly cold last night . . . I cannot say where we are, but it is “somewhere in Belgium”.. . I passed through a fair-sized town coming here yesterday, and I don’t think there was one undamaged house; the churches, etc., were in ruins. . . . It is not so bad out here; it is cold at nights and very uncivilised, and after a bit I should think the strain will be a bit of a nuisance, but taking things all round it might be heaps worse.

His last letter, dated November 13th, written to a younger brother:

The front line is in an awful state for water, well over knee deep; we all have to wear long rubber boots like fishermen’s waders, right to the top of your legs, to get along at all. Supplies, etc., have to come over the open, bullet-swept ground by night, as the communication trench is waist deep in water and liquid mud, and is impassable except for very small parties without any load. We had no rations sent up for two days; the first day we had breakfast, dinner and tea of bread and butter, tea and jam. We knocked off dinner at night! . . . We never move without our smoke helmets in case of gas, and are never supposed to move singly, always at least two. You might have an extra bath for me; we can’t even get a wash, shave or anything here; it means going about like tramps all the time you are in the front line. I haven’t washed for four days, and have quite a beard now! It is fearfully funny. I must look a sight judging from the others; but we have not a looking-glass fortunately! . . . . We simply yell with laughter when we look at each other.