In February 2016 I gave a talk about the archives as part of the Thursday lunchtime Recital Room series. I’ll put the talk on the blog in a series of posts. The third installment is below. Click here for the first installment (about Arthur Rowntree’s views about leisure activities) and here for the second installment (about cricket).

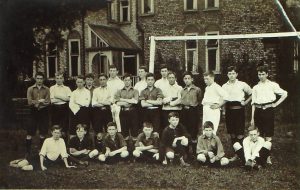

According to the 1923 School History, Football was introduced to the school by John Ford on 13th October 1862. According to James Edmund Clark, “John Ford had been on pilgrimage to Rugby, to behold the scenes familiar through the life of his great favourite, Dr. Arnold. Finding how rarely serious harm resulted there, he decided to remove the embargo at Bootham. So one day, soon after twelve o’clock, the bell summoned us to “collect.” The lines were unusually straight and wondering, for at the head stood John Ford, with the “forbidden thing” in his hand. Had anyone smuggled it in? No! he told us all about it, gave us our first ball and himself the first kick, straight as an arrow between the lines.” H.M Wallis does point out though in his chapter in the 1923 School History that the rules were somewhat vague, although this is unsurprising at a time when the rules of the game were still being codified, and there would have been many versions around. He says “we knew not whether to put the ball over or under the bar, or if handling was allowed.” It is however possible that a version of football had been played at some earlier point – George Scarr Watson, who was at the school between 1853 and 1858 mentioned that a broken rib or arm had put an end to football before his time – he saw it later as a “merciful dispensation of Providence. How many journeys to witness cup finals I have escaped; also colds and chills and pneumonias caught in watching that astonishing game.”

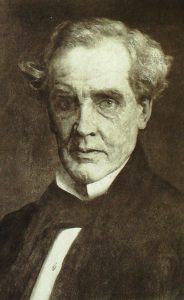

Arthur Rowntree, who was a student at the school in the 1870s and went on to become Headmaster, remembered the first football match with an outside team—”we played in ordinary clothes and counted the enemy snobs for changing.” He also remembered how there were 60 boys in the school when he started, and they all played football together in ordinary weekday clothes—North v. South, Senior v. Schoolroom—and thankful we youngsters were if we touched the ball once during the hour.”

Gradually the game became established, and when the magazine started in 1902, football team reports appeared. The team notes were written by the captain, and were notable for their honesty. An extract from 1903 gives an example:

“We began the season with an unusually young and inexperienced line of forwards. They improved as the season went on. But as three of them are to be with us next season we may be excused mentioning a few of their faults, in hopes of still further improvement—-

- Standing in an impossible position to receive a pass and staying there.

- Receiving a ball facing wrong way, so that the opposing half easily forces them towards their own goal or into touch.

- Slowness in taking advantage of openings in front of goal.

- Lack of strenuousness.

- Want of pace.”