In January I did a talk as part of the Thursday lunchtime recital room series. It was entitled ‘Memories from the Archives’ and I talked about a number of memories from Old Scholars. I’ll share the photographs and text from the talk in several parts on the blog. Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here and Part 4 here.

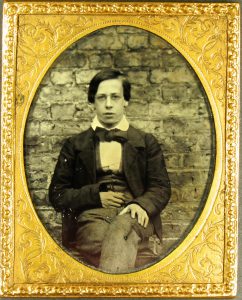

James Edmund Clark (1850-1944; Bootham 1862-67; Master at Bootham 1869-72 and 1875-97)

James Edmund Clark was at Bootham in the 1860s and returned as a Science Master. According to Natural History at Bootham – the Early Years, he was the first graduate to be appointed to the staff and the first person to be appointed specifically to teach science at the school. In an article for ‘Bootham’ magazine in 1903, he talks about the language used, the classroom arrangements, town leave, columns and top-hats.

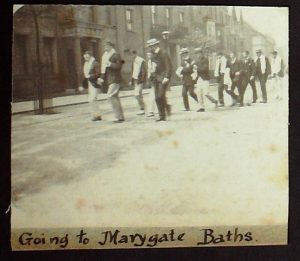

“Quaker-boys ways were plainer then. ‘Thee’ and ‘thou’ was the universal language, and, except John Ford, masters had to be satisfied with their Christian names. It was ‘Silvanus’ and ‘Alfred’ and ‘Theodore’ and even ‘Fielden’. Well do I remember the light which dawned upon certain untutored minds, when it was suggested that, at public places, like the baths, ‘Thomas please’ would sound politer with the surname sandwiched in.”

Talking about the schoolroom, “One row of desks was under the playground windows, from the ‘altar’ to Silvanus Thompson’s desk. The central desks were in pairs of four or five each, back to back. On the other side was Mr Fryer’s desk, Silvanus Thompson’s serviceable ‘shop’, contained in the drawers of a table, while the junior master’s desk stood under the central window. Near him dwelt his little flock, their lessons frequently going on here with another class at either end. Their only retreat was the ‘junior class-room’ next to the old ‘senior’, and this was not always habitable. For it served, also, as natural history room, without possessing all the conveniences of the latter for the bestowal of refuse matter. The only receptacle, indeed, for such articles was an ominous looking black-ware vessel in the darkest corner, which only too fitly merited its suggestive title of ‘stink-pot’. Moved by that strange but apparently resistless attraction for doing the thing which should not be done, some small boy almost invariably ventured to give it a stir.”

Moving on to town-leave, he says “How altered is ‘town leave’ now! Six keys, later eight, used to hang up inside the library, and twice a day that number of boys might go out. ‘Mrs Gray’s, please’. ‘Thou mayst; not more that twopence’ was the usual formula. Little hope for a juvenile to be one of the six or eight, the eldest coming first.”

James also remembers columns (including the first half a dozen words on the list), and remembers that “My unluckiest day … was the equivalent of fifteen columns. Two of these were for whistling in the passage; three for leaping the railings of the boys’ gardens; ten for aspiring to the Observatory roof.” This would have been the old observatory, rather than the current one in the science block.

He also remembers that “The Half of my arrival witnessed also that of the first top-hat known in Bootham School. As the wearer measured 6 feet 2 inches in his stockings the effect was that of a city set on a hill. The infection caught on, until, before I left, half the school were victims of the unfortunate fashion.”